Philosophy Colloquium Series

Michael Cohen

Tillburg University,

Assistant Professor of Philosophy

November 7, 2025

2PM - 4PM, CTIHB 459

Luca Ferrero

University of California, Riverside

Associate Professor of Philosophy

October 31, 2025

2PM - 4PM, CTIHB 101

Sandra Shapshay

Hunter College/CUNY Grad. Center,

Deputy Executive Officer and Professor of Philosophy

October 17, 2025

2PM - 4PM, CTIHB 101

Travis N. Rieder

John Hopkins University

Associate Research Professor January 10, 2025

2PM - 4PM, CTIHB 459

Carolina Flores

UC Santa Cruz,

Assistant Professor of Philosophy

November 22, 2024

2PM - 4PM, CTIHB 459

William D'Alessandro

William & Mary,

Assistant Professor of Philosophy

September 20, 2024

2PM - 4PM, CTIHB 459

Stephanie Partridge

University of Iowa,

Adjunct Lecturer in Human Rights

March 28-29, 2024

Kathleen A. Creel

Northeastern University,

Assistant Professor of Philosophy, Religion, and Computer Sciences

March 14-15, 2024

Asad Ahmed

University of California,Berkeley,

Distinguished Professor of Arabic and Islamic Studies

February 29, 2024

Sally Haslanger

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Ford Professor of Philosophy & Women's and

Gender Studies

February 4, 2022

Katherine Furman

University of Liverpool, Philosophy, Politics and Economics Lecturer

October 22, 2021

Elliot Samuel Paul

Queen's University, Assistant Professor of Philosophy and Arts and Science

March 19, 2021

Madison Kilbride

University of Pennsylvania, Instructor of Medical Ethics and Health Policy

February 19, 2021

Julia Bursten

The University of Kentucky, Assistant Professor of Philosophy

* Canceled due to COVID-19

Lanier Anderson

Stanford University, J.E. Wallace Sterling Professor of the Humanities

November 8, 2019

To be added to the Colloquium Series list, please contact philosophy@utah.edu!

Paul C. Taylor

Vanderbilt University

September 30, 2022

2:30pm - 4:30pm

In-Person

Uneasy Sanctuaries: Rethinking Race-Thinking

Abstract:

In the introduction to his remarkable book, Shadow and Act, Ralph Ellison identifies one of the stumbling blocks to successful "Negro" fiction.

The problem, he suggests, is "the writers' refusal... to achieve a vision of life

and a resourcefulness of craft commensurate with the complexity of their actual situation."

(Collected Essays of Ralph Ellison 59). What does this refusal lead to? "Too often," Ellison explains, writers "fear to

leave the uneasy sanctuary of race to take their chances in a world of art."

Ellison's diagnosis, or something like it, applies with equal force to philosophers.

We are also prone to treating real-world complexity as something that sullies or sidetracks

the work of philosophy, especially when that complexity arises from the swirl of intersecting

conditions that work through and with the forces of racialization. For us, too often,

race is just the first sanctuary, and our attempts to escape it lead us to other places

of refuge, to other ways of evading the vicissitudes of embodiment, location, finitude,

and politics.

I propose to explore the itinerary of evasion that can result from philosophical attempts

to take race seriously. This itinerary will run through a variety of uneasy sanctuaries,

starting with race itself and winding through disciplinarity, canonicity, heretical

theory, and prophetic witness. The aim will be to highlight some underappreciated

challenges to the work of philosophical race theory and to cultivate a responsible

orientation to the work in light of its challenges.

Justin Garson

Hunter College and CUNY Graduate Center, Professor of Philosophy

September 2, 2022

What are mental disorders?

Abstract:

The most developed and well-defended account of mental disorder is Jerome Wakefield’s

Harmful Dysfunction Account (HDA), which holds that when someone has a mental disorder,

something inside them can’t perform its evolved function, and this inability has harmful

consequences. There are three positions that philosophers have taken on the HDA: as

being true, as being false, or as a potentially useful linguistic framework. Here,

I identify a fourth stance, that of the conceptual genealogist: what is the point

of the HDA? What is it designed to do? Historically, its purpose was to give voice

to a specific biomedical paradigm that I call “madness as dysfunction,” a paradigm

I believe to be harmful. From this vantage point, the question of the HDA’s truth

status becomes relatively uninteresting. The interesting question is: what are some

strategies for combatting the pernicious influence of that paradigm while giving voice

to, and thereby promoting, others?

Mike Conway

University of Utah, School of Medicine

September 14, 2018

Abstract:

This talk will discuss (a) recent work on utilizing social media as a resource for understanding mental health, and (b) ethical issues involved in the use of social media for health research.

Marko Malink

Associate Professor of Philosophy and Classics at NYU

November 9th 2018

Aristotle on Demonstration by reductio ad impossibile

Abstract:

In the Posterior Analytics, Aristotle develops a theory of scientific knowledge and demonstration. He argues that direct demonstrations are superior to demonstrations by reductio ad impossibile on the grounds that the former, but not the latter, proceed from premises which are prior in nature to the conclusion (Posterior Analytics 1.26). While this view has been widely influential throughout the history of philosophy, Aristotle's argument for it is not straightforward and has been deemed problematic since antiquity. The purpose of this talk is to shed new light on this argument. I argue that it relies on a specific relation of priority in nature among scientific propositions that is determined by the theory of predication presented in Posterior Analytics 1.19-23. I show how this relation of priority in nature allows us to make sense of Aristotle's thesis concerning demonstration by reductio ad impossibile. I conclude by indicating how Aristotle's thesis is related to analogous results in contemporary theories of grounding.

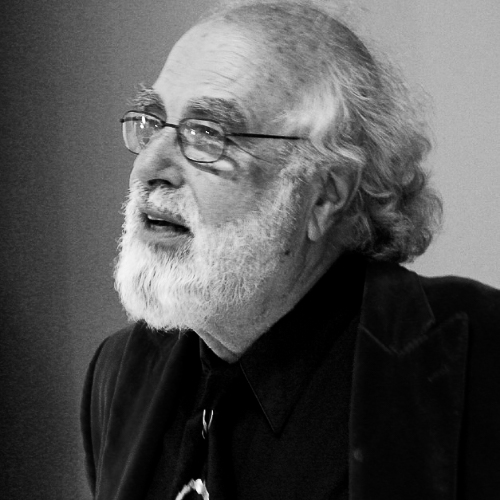

Robert Pippin

Distinguished Service Professor

The University of Chicago

December 7, 2018

Is There a Philosophical Point to Nietzsche's Literary Style? The 'New Philosophers' in Beyond Good and Evil'

Abstract:

The subtitle of Nietzsche’s Beyond Good and Evil is Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future. This immediately suggests that there must be a new form of philosophy and that all the philosophy of the past has somehow come to an end, even though that form is, however new, still a form of philosophy. But such a new form also involves a different form of writing; highly literary, episodic, often metaphorical, paradoxical, and sometimes intensely passionate. Why the philosophy of the future should have, perhaps must have, such a literary form, and what bearing that form might have on an attempt to answer what still appear to be philosophical issues (e.g., “perspectivism” and “The Will to Power”), are the twin foci of this discussion.

Jennifer Blumenthal-Barby

Baylor College of Medicine

January 18, 2019

Exploring the Ethics of Nudging in Medicine

Abstract:

I argue that the fact that patients' decisions are often non-autonomous (or autonomy impaired), poor quality, and harmful to them and their interests permits, or even requires, using principles from behavioral economics and decision psychology to shape, nudge, ore engage in "choice architecture" of thier decision making.

Subrena Smith

University of New Hampshire, College of Liberal Arts

February 1, 2019, 2:30 pm - 4:30 pm

More Differences than Kinds

Abstract:

It’s the norm in nature for organisms to exhibit traits that are uncommon amongst members of their kind. Deviations away from species-typical traits can be understood in different ways: near-term survival benefits or longer-term survival benefits. Human beings, like other living systems, exhibit traits that are different from some of the norms for some human beings. Against views that emphasize human similarity, this talk offers reasons for emphasizing difference.

Naomi Oreskes

Harvard University, Professor of the History of Science

February 11, 2019, 4:30 pm - 5:30 pm

GC 1900

"Scientific Consensus, Climate Change, and the Role of Uncertainty in Science"

(Jointly hosted with Society, Water & Climate Research Group). Oreskes is the co-author of "Merchants of Doubt," and Professor of History of Science at Harvard University. We hope you are able to join us!

Kathryn Tabb

Bard College, Assistant Professor of Philosophy

April 5, 2019

2:30 pm - 4:30 pm

Tanner Library, Room 459

Abstract:

Popular television shows, novels, and science writing about forensics and the law often rely on a widely-held intuition: that when behaviors are discovered to be caused by genetic dispositions, people consider them less blameworthy. And in real-life contexts like the courtroom, genetic information is increasingly brought to bear in order to mitigate punishments for antisocial or violent crimes. Yet, psychologists have not been able to produce this intuition in the laboratory setting as robustly as one might expect – indeed, there is very little empirical work showing any such effect at all, with most studies showing genetic information to have no significant effect on moral judgments. In this talk I present some empirical data suggesting why this might be the case. Results from recent studies show that people seem unwilling or unable to accept genetic explanations for antisocial behavior, while comparable explanations for prosocial behavior are accepted without equivalent resistance. In other words, before experimental subjects even get to the step of integrating genetic information about bad actions as part of their assessments of moral responsibility, they have already discounted its worth. My first aim is to consider what might cause this asymmetry, and what it might indicate about how common moral intuitions affect the way genetic information is received by non-specialists. My second aim is to consider some philosophical (and some practical) repercussions of these findings.

Keith Lehrer

The University of Arizona, Regents Professor of Philosophy, Emeritus

August 23, 2019

Keith Lehrer is Regent's Professor emeritus of Philosophy at the University of Arizona and a Research Professor of Philosophy at the University of Miami in Florida, where he spends half of each academic year.

Lehrer will be speaking as part of the Philosophy Colloquium Series.

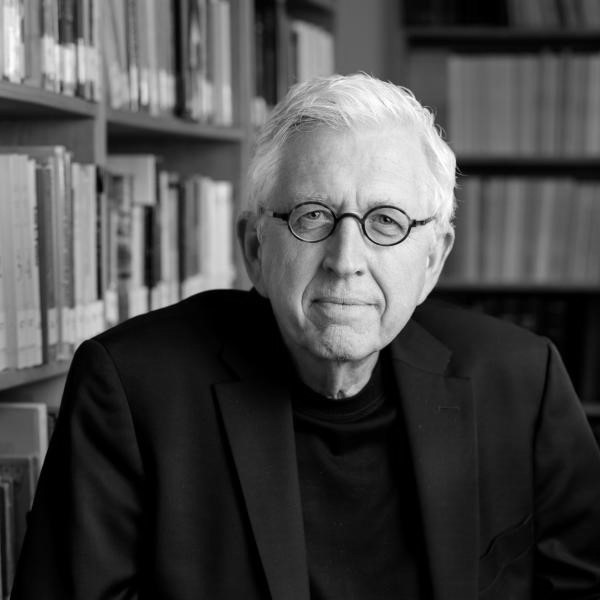

R. Lanier Anderson

Stanford University, J.E. Wallace Sterling Professor of the Humanities

November 8, 2019

2:30 pm - 4:30 pm

Tanner Library, CTIHB 459

Nietzschean Autonomy and the Meaning of the ’Sovereign Individual'

Abstract:

This paper has two goals—a narrow one which I take myself to achieve, and a more ambitious one toward which I can make only preliminary suggestions. The limited goal is to resolve an interpretive dispute over Nietzsche’s intentions in the Genealogy’s description of the “sovereign individual,” a character type whose features turn out to have important bearing on Nietzsche’s distinctive conceptions of conscience, promising, and what it is to take responsibility for oneself. The more ambitious goal is to characterize what Nietzsche means by autonomy and to assess what we might have to learn from his conception. The paper’s basic idea is that the meaning of the sovereign individual emerges clearly in the light of a distinction from Bernard Williams between two senses of responsibility—one sense tied to voluntary action, the other to an ambitious conception of responsible agency. What we learn about responsibility from Williams then illuminates how we should understand Nietzschean autonomy, and what philosophical purposes his conception can (and cannot) serve.

Jonathan Herman

Georgia State University, Associate Professor of Religious Studies

November 15, 2019

2:30 pm - 4:30 pm

Tanner Library, Room 459

Julia Bursten

The University of Kentucky, Assistant Professor of Philosophy

* Canceled due to COVID-19

Canceled due to COVID-19.

Sally Haslanger

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Ford Professor of Philosophy & Women's and

Gender Studies

* Canceled due to COVID-19

Canceled due to COVID-19.

Michael O' Rourke

Michigan State University, Professor of Philosophy

October 23, 2020

2:30 pm - 4:30 pm

Zoom

Is there any hope for interdisciplinarity?

Abstract:

Interdisciplinarity has been an important mode of knowledge organization for decades, but there remains a diversity of opinion about what it is. I’ll begin this talk by considering reasons why this might be so before describing two paths to consensus: one constructive and one skeptical. The constructive path embraces the orthodox view that integration is key to understanding what is involved in interdisciplinary practices. I’ll develop the idea of interdisciplinary integration in some detail and point to a few open philosophical problems. The skeptical path embraces the lack of consensus as a sign that there is no there there, so long as interdisciplinarity is characterized in traditional ways. I’ll close by arguing that these paths intersect and that we should strive to locate work on this topic in that intersection.

Anne Eaton

University of Illinois Chicago, Associate Professor of Philosophy

February 19, 2021 *

* Postponed to 2022

Postponed to 2022. To be announced.

Tina Rulli

University of California, Davis Associate Professor of Philosophy

February 26, 2021

2:30 pm - 4:30 pm

Zoom

Positive Symmetry in our Procreative Reasons

Abstract:

I assume that we have moral reason not to create miserable people, and I motivate the view that we have moral reason to create happy people. This is a rejection of the famous Procreative Asymmetry in favor of what I will call Positive Symmetry. Nonetheless, I also argue that our moral reason to create happy people is weaker than our moral reason not to create miserable people. I suggest ways in which it might be defeated in the actual world. Its relative weakness and vulnerability to defeat might explain why many people have the intuition that we have no such reason in the first place, and thus they endorse the Asymmetry. Given the theoretical difficulties with defending the Asymmetry, Positive Symmetry may be an attractive alternative. Defending Positive Symmetry with a weaker reason to create happy people than not to create miserable people makes this position more intuitively acceptable than it may first seem. I also suggest that even if Positive Symmetry is the correct view and there is reason to create happy people, this reason may nonetheless be defeated in our actual world. Thus, a pro-natal anti-natalism is possible.

Elliot Samuel Paul

Queen's University, Assistant Professor of Philosophy and Arts and Science

March 19, 2021

2:30 pm - 4:30 pm

Zoom

Cartesian Inference

Abstract:

What is inference? Descartes has a remarkably nuanced answer to this question, but it has been misunderstood. On the standard reading, Descartes thinks an inference is merely a causal process in which intuiting some propositions causes you to intuit others. I argue that, instead, Descartes construes an inference as a clear apprehension that an argument is sound. This is a complex state in which your apprehension of the premises and conclusion are fused together by your apprehension of the entailment between them, such that the conclusion is illuminated or made clear by the premises. A major benefit of this view is that it can be used to solve Lewis Carroll's famous regress problem for inference.

Madison Kilbride

University of Pennsylvania, Instructor of Medical Ethics and Health Policy

February 19, 2021

2:30 pm - 4:30 pm

Zoom

Ethical Issues in Direct-to-Consumer Genetic Testing: A New Approach to Studying Consumer Experience

Abstract:

Direct-to-consumer (DTC) genetic testing companies now offer tests that have significant implications for consumers’ health. Notably, these companies employ a new business model in which tests are advertised to consumers but ordered by licensed physicians. In most cases, these physicians are provided by the company and have no existing relationship with the individual seeking testing. In this talk, I consider some of the ethical concerns raised by this type of testing. I then discuss my NIH grant project, which seeks to evaluate whether the risks identified in my conceptual work are reflected in consumers’ actual experiences with testing. Finally, I explore how my project’s empirical data could inform our thinking about the ethical issues surrounding this new model of DTC genetic testing.

University of Liverpool, Philosophy, Politics and Economics Lecturer

October 22, 2021

2:30 pm - 4:30 pm

Zoom

Epistemic Bunkers

Abstract:

One reason that fake news and other objectionable views gain traction is because they often come to us in the form of testimony from those in our immediate social circles; from those we trust. A language around this phenomenon has developed which describes social epistemic structures of “epistemic bubbles” and “epistemic echo chambers”. These concepts involve the exclusion of external evidence in various ways. While these concepts help us see the ways that evidence is socially filtered, it doesn’t help us understand the social functions that these structures play, which limits our ability to intervene on them. In this paper, I introduce a new concept – that of the epistemic bunker. This concept helps us better account for a central feature of the phenomenon, which is that exclusionary social epistemic structures are often constructed to offer their members safety, either actual or perceived. Recognising this allows us to develop better strategies for mitigating their negative effects.

Olúfemi Táíwò

Georgetown University, Assistant Professor of Philosophy

October 29, 2021

2:30 pm - 4:30 pm

Zoom

Subjective Security

Abstract:

The distinction between "negative" and "positive" freedom focuses on the political and ethical subject's relationships with herself and with other people. Materialists have tended to focus more on the direct contribution of the social circumstances in which the subject finds herself (e.g. her relationship to the means of production and the means of subsistence). In this talk I try out one strategy for reconciling the former focus with the latter, one rooted in the political ideal of self-determination, which I associate with the latter group of thought. I'll attempt to describe subjective security as a resource that allows a person to extend herself across time, institutions, and persons in ways that are vital for securing her freedom, and sketch some political implications of this view.

Karen Kovaka

Virginia Tech, Assistant Professor of Philosophy

November 19, 2021

2:30 pm - 4:30 pm

In-Person

Environmental Interference

Abstract:

A child born in 2021 will witness the extinction of up to one-third of all plant and animal species by their fiftieth birthday. It is counter-intuitive, yet true, that the most promising conservation responses to this ecological crisis often involve drastic interference in nature. Consider Predator-Free 2050, a nationwide policy of air-dropping poisoned baits across New Zealand each year in an effort to eradicate the invasive rats, stoats, and possums that prey on the country’s endangered bird species. This and many other conservation strategies are in deep tension with the influential environmentalist idea that we should leave nature alone, wherever and whenever we can, because nature is unpredictable, and even well-intentioned interventions are likely to have harmful unintended consequences. This idea is the presumption against environmental interference. I argue that the presumption against environmental interference is not and cannot be justified as an epistemic principle, and I offer alternative principles that can serve as better guides in conservation research and decision-making.

Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Ford Professor of Philosophy & Women's and Gender Studies

February 4, 2022

2:30 pm - 4:30 pm

Zoom

The Materiality of the Social World: Bodies, Resources, and the Environment

Abstract:

Consider a social event such as eating a meal together. The existence of this event depends not just on human minds (collectively engaged or not), but also on human bodies and edible stuff that has been produced, distributed, prepared, and served according to local customs. Human bodies and their environment – plants, stoves, recipes, plates – both set constraints on the social world and are, at the same time, part of it. An individualist social ontology places tremendous emphasis on the power of “collective intentionality” to constitute the social world. But our powers are limited by the material conditions, our embodiment, our ignorance, the accidental bad effects of good intentions (not to mention the bad intentions), and the fragmentation of societies. This paper sketches an account of social systems, including, e.g., transportation systems, health-care systems and the like, that incorporates multiple elements – material, cultural, historical, psychological – affecting our forms of coordination. This view requires us to rethink the assumption that mind-dependence is distinctive of sociality.

Nico Orlandi

UC Santa Cruz,

Professor of Philosophy

February 18, 2022

2:30 pm - 4:30 pm

In-Person

Labels in Thought

Abstract:

Standard accounts of concepts in philosophy and in cognitive psychology assume a symmetry between the representational complexity of the process of concept-attainment and the representational complexity of the product of such attainment. Only concepts that are complex or structured are generally taken to be learned. If a concept is atomic or unstructured, on the other hand, then it is thought to be triggered or “occasioned” by experience, and this triggering is supposed to be a process that does not make use of representations. I argue that we should reject this commonly accepted symmetry between process and product. I offer examples of how complex concepts might be learned from processes that are not representationally complex. I also demonstrate the converse, showing how we could learn simple concepts through representationally complex processes, specifically using the notion of an object-file. This problematization of the symmetry between the process and products of concept-acquisition means that the learnability of a concept is not an indicator of its structure; this, among other things, supports reviving an atomistic view of concepts, according to which concepts are akin to labels in thought.

Anne Eaton

University of Illinois Chicago,

Associate Professor of Philosophy

April 22, 2022

2:30pm - 4:30pm

In-Person

How to Do Things with Pictures

Abstract: TBA

Şerife Tekin

University of Texas at San Antonio,

Associate Professor of Philosophy

October 7, 2022

2:30pm - 4:30pm

In-Person

Unmuting Patients in Psychiatric Epistemologies: Insights from the Opioid Crisis

Abstract:

One of the central aims of psychiatry is to identify the properties of mental disorders

to enable their diagnosis and treatment. As a branch of both science and medicine,

psychiatry draws on a variety of scientific and medical practices to glean information

about these properties. These practices include scientific research on mental disorders,

such as clinical drug trials for depression treatment, as well as clinical research,

such as case studies on treatment resistant depression. The goal is to develop effective

interventions into mental disorders. While the first-person experience and reports

of individuals with mental disorders provide unmatched resources for investigating

the properties of mental disorders and designing effective interventions, dominant

psychiatric frameworks have not systematically included patients in the scientific

inquiry. Patient communities are rarely considered “subjects” who produce knowledge.

Rather, patients are “objects” of investigation, e.g., when they are recruited for

clinical trials. In this talk, using insights from research, treatment, and patients’

testimonies on Opioid Use Disorder, I argue there are epistemic – rather than exclusively

social/political – reasons for including individuals with mental disorders in psychiatry’s

efforts to identify the properties of mental disorders.

Ezgi Sertler

Utah Valley University,

Assistant Professor of Philosophy

November 11, 2022

In-Person

Structured Failures: Knowing in Asylum

Abstract:

Asylum regimes house both credibility-related and intelligibility-related forms of

epistemic injustice – such as testimonial and contributory epistemic injustice– under

their roofs. From first-level interviews to courtrooms, decision-makers persistently

not only fail to believe applicants but also fail to understand them and make sense

of their lives, realities, and experiences. While such interactions between asylum-seekers

and decision-makers render perceivable significant and persistent epistemic exclusions

asylum seekers suffer from, understanding the epistemic landscape of asylum regimes

goes beyond these interactions. In this paper, I aim to shed some light on the constitutive

elements of this epistemic landscape. It is my hope to demonstrate that the epistemically

unjust situations asylum seekers are forced into can help us unearth how this uneven

playing field is structured. This paper, while noting the parallels between different

institutions of asylum in different countries, investigates the institutionalized

practices of asylum in the U.S. more closely. In what follows, I will identify, at

least, four constitutive elements of the epistemic landscape of the asylum regime

in the U.S.: 1. range of epistemic affordances, 2. question of epistemic agency, 3.

governance of comprehensibility, and 4. assignment of worth.

Devin Sanchez Curry

West Virginia University,

Assistant Professor of Philosophy

January 27, 2023

In-Person

Scientific Psychology for Folk Craft: The Case of IQ

Abstract:

Philosophers of mind (from eliminative materialists to psychofunctionalists to interpretivists) generally assume that a normative ideal delimits which mental phenomena exist (though they disagree about how to characterize the ideal in question). I want to chip away at this widely shared assumption. In particular, I’ll argue that a comprehensive ontology of mind would include some mental phenomena that are neither (a) explanatorily fecund posits in any branch of cognitive science that aims to unveil the mechanistic structure of cognitive systems nor (b) ideal (nor even progressively more ideal) posits in any given folk psychological practice. Indeed, one major function of scientific psychology has been (and will be) to introduce just such (normatively sub-optimal but real) mental phenomena into folk psychological taxonomies. The development and dissemination of IQ research over the course of the 20th Century is a case in point.

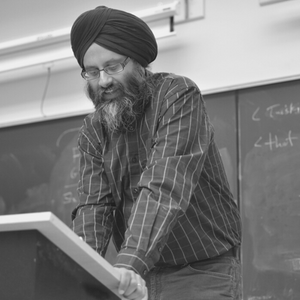

Gurpreet Rattan

University of Toronto,

Professor of Philosophy

February 10, 2023

In-Person

I Think, Therefore I Am Not

Abstract:

Descartes thought that he could conclude based on his occurrent thinking that he himself exists, as a thinking thing. Lichtenberg and Russell objected that Descartes was entitled to conclude a judgment, not that he himself exists, but only that there is thinking going on. Kant and Wittgenstein envisioned a middle position, according to which I am not intuited in receptivity but apperceived in spontaneity (Kant), and in which I would not appear in my book, should I have written it, The World as I Found it, but instead would be a “limit” to the world that there would be described (Wittgenstein). These ideas set up a framework for thinking about the metaphysics of the self in terms of what I call three grades of self involvement, where the transition from one grade to another involves increasing levels of metaphysical commitment. I explain this framework, articulating it in relation to some contemporary work on the metaphysics of the self, and then use it to argue for my own, second grade, view. The argument I give against moving to the third grade is based in epistemological/philosophical and not scholarly considerations. The argument concerns the principled, necessary limits that the self, understood as a subject of judgments, encounters when it tries to make objective judgments about itself that are supposed to inform its judgments about the world. One consequence of my argument is that Descartes should have said cogito ergo non sum. Yes, I can conclude from my occurrent thinking that I am thinking, but precisely because of this, I cannot be a thing in the world that I am thinking about.

Crystal Rudds

University of Utah,

Assistant Professor of English

March 31, 2023

In-Person

Home/Being: Public Housing Subjects in Photography

Abstract:

This paper asks in the vein of Kevin Quashie how do “quiet” narratives of Black men’s domesticity deepen how we understand what it means to dwell? Analyzing images wherein the subject subverts the gaze and the associated pathology of public housing, Rudds considers the manifold nature of black life as analogy for the privacy of interiority’s ephemera.

Moriel Zelikowsky

University of Utah,

Assistant Professor of Neurobiology

March 24, 2023

In-Person

Abstract: TBA

Robyn Bluhm

Michigan State University,

Associate Professor of Philosophy

September 22, 2023

In-Person

Deep Brain Stimulation, Electroconvulsive Therapy, and the Self.

Abstract:

Deep brain stimulation (DBS) therapy uses electrodes implanted in the brain to treat several neurological disorders, and it is also being investigated for a variety of psychiatric conditions. After a small number of case reports suggesting that some people treated with DBS feel like a different person, neuroethicists have debated the nature of these self-related changes. I have argued that these debates are overblown, and now suggest that we can get a better understanding of these changes in two ways. First, we should broaden the discussion to consider patients’ experiences of other kinds of neurostimulation, particularly electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). Second, the philosophical literature on narratives and the self-offers resources beyond those that neuroethicists have tended to discuss, which offer a more helpful way of thinking about how neurostimulation therapies affect people using these therapies.

Anne Peterson

University of Utah,

Associate Professor of Philosophy

October 20, 2023

In-Person

A Lost Discipline? Nature, Divinity, and Priority in Aristotle’s Sciences

Abstract:

Aristotle articulates the need for distinctive methods in natural science and mathematical science. These methods allow him to develop new foundations for sciences not recognized by his predecessors, such as biology. As part of this general framework of sciences, however, Aristotle articulates the importance of a further science: what he calls the first science. What does the first science study, and how is it related to other sciences? The scholarly literature on this issue commonly understands Aristotle’s first science to be theological and separate from natural science. But such views overlook the true nature of this science, leading to a misunderstanding not only of it but also of the other sciences. I will show that the first science is, for Aristotle, a general discipline that opens the door to the systematic development of new sciences. This new interpretation of Aristotle’s first science underscores its overlooked relevance for the sciences today.

Jan Forsman

University of Iowa,

Post-Doctoral Researcher in Philosophy

November 17, 2023

In-Person

Margaret Cavendish and Skepticism

Abstract:

Margaret Cavendish’s (1623–1673) theories of sense perception and epistemology have been a debated matter in the recent commentary literature (e.g., Boyle 2015; Cunning 2016; 2023; Hock 2018; Georgescu 2020). While interest in these parts of Cavendish’s philosophy has increased, especially after Michaelian’s article (2009), much of the discussion has concentrated on perceptive self-knowledge in relation to other parts of matter, while her epistemological stands have still received little attention, with no emerging consensus. Cavendish has been described as a rationalist, an empiricist, seeking an alternative between rationalism and empiricism, not having an epistemological theory in the first place, and a skeptic. While Cavendish’s possible skepticism has been mentioned occasionally (e.g., Sarasohn 1984; 2010; Brown 1991; Clucas 2003; Boyle 2015; Hock 2018; Sherman 2021; 2023), there has thus far not been a concentrated discussion on her relationship with skeptical thinking. However, since the skeptical movement of the time motivated both Cartesian and non-Cartesian philosophies in Cavendish’s period, her relation to skepticism deserves a closer look.

I discuss Cavendish’s relation to skepticism, especially in Observations Upon Experimental Philosophy (OEP, 1666), where she comments on ancient skepticism of the Pyrrhonians and the Academics. I relate these remarks to her other works like Poems and Fancies (1653), Philosophical and Physical Opinions (1655), The Blazing World (1666), and Grounds for Natural Philosophy (1668), while contextualizing the historical background of Cavendish’s knowledge of skepticism from the Cavendish Circle and intellectuals surrounding it, like Pierre Gassendi (1592–1655) and Walter Charlton (1619–1707), as well as Joseph Glanvill’s (1636–1680) Scepsis Scientifica (1665) and Thomas Stanley’s (1625–1678) History of Philosophy (1655–1660). I argue that Cavendish is sympathetic to skepticism, especially the probabilistic skepticism of the later Academics. She can then be read as supporting a stance of ‘mitigated’ skepticism towards natural philosophy and science, in which she is fully skeptical of certain fields while asserts the importance of scientific inquiry on others, such as the study of particulars, but views that study to be based on speculation with little epistemic ground.

Keisha Ray

UT Health Houston,

Tenured Associate Professor of Humanities and Ethics

April 12, 2024

In-Person

The Inhumanity of Environmental Racism and What It Means For Bioethics and Black Health

Abstract:

The consequences of our unhealthy environment are not felt equally, with people in the global south, people with low incomes, and people of color disproportionately shouldering the consequences of changing climates and toxins and carcinogens in our air and water. Black people in particular, see their health intimately intertwined with unhealthy environments and the social institutions that maintain this unhealthy relationship. In this presentation I discuss examples of environmental racism in the United States and how this instance of social inequity contributes to Black people’s generally poor health. This discussion will show the importance of making environmental racism central to how bioethicists speak about health equity in general, and how we ought to think about structural anti-Black racism’s role in maintaining racial disparities in health outcomes.

William D'Alessandro

William & Mary,

Assistant Professor of Philosophy

September 20, 2024

In-Person

2PM - 4PM, CTIHB 459

Imagination, Methodology, and Ontology (joint work with Alice Murphy, Munich Center for Mathematical Philosophy)

Abstract:

This paper explores unexamined uses of imagination in mathematics by bringing together examples from mathematics with debates on the epistemic value of imagination. We move beyond the widely acknowledged role of imagination and images as cognitive aids to consider three cases of imagination serving as a purported source of mathematical knowledge: (i) Chris Freiling’s dart-throwing thought experiment against the Continuum Hypothesis, (ii) imaginability in ontological debates surrounding infinite numbers from the early moderns to Cantor, and (iii) Leibniz’s use of infinitesimals in analysis. These examples exemplify how the mathematical domain offers intriguing and methodologically distinctive uses of imagination. They demonstrate the need for philosophers of mathematics to pay attention to imagination in mathematical practice, and their exploration enriches the rapidly growing literature on imagination (and related states such as conception and supposition).

Kilian Jorg

October 18, 2024

In-Person

2PM - 4PM, CTIHB 459

An Ecology of Moralizing

Abstract:

Why is "moralizing“ mostly regarded as a pejorative conversation ender today? How did this start? The term is often – especially from the left – seen as the purview of the pursed-lips privileged prude that are disregarding the material grounds and social complexities of capitalist life. To be moralizing is to be naive, preposterous and even apolitical. Thus, while most want to be ethical humans, few want to appear to be moralizing under any circumstances. In this presentation, we examine how we have gotten to this point and if moralizing is happening whether we want it or not. We ask if a rejection of moralizing as judgemental condemnation is perhaps in itself anoversimplification neoliberal philosophy thrives on. By reviewing radical sources of anarchist moralizing, we want to reformulate it as a situated, concrete form of custom- and community-building in a shared planetary situation of ongoing catastrophe. We argue that this kind of moralizing might be essential for the long breath that transformative politics require in today’s dire situation.

November 1, 2024

In-Person

2PM - 4PM, CTIHB 459

Social-Ecological Triage: Environmental Justice and Future Catastrophes

Abstract:

Despite the prevalence of the triage concept within multiple disciplines (e.g., bioethics and conservation biology), discussions do not provide guidance with respect to catastrophes that occur at the intersection of social systems and ecosystems (social-ecological systems (SESs)). SES triage after a catastrophe is complicated because the stakeholders are diverse and ecosystem services are multifaceted. Success depends on investments in both the social and the ecological dimensions of SESs across spatiotemporal scales. Thus, SES triage presents significant ethical challenges at a time when catastrophes are more frequent and more intense due to climate change. This essay is an attempt to better understand environmental justice within the context of SES triage. The thesis is that environmental justice in SES triage involves two interconnected steps: (1) identification of at-risk populations and (2) communication of latent hazards between the at-risk populations and the institutions responsible for the allocation of resources after a catastrophe. It is suggested that geographical context might facilitate the process since latent hazards are evenly distributed across space. The Great Salt Lake (UT, USA) is examined as a potential example case.

January 10th, 2025

In-Person

2PM - 4PM, CTIHB 459

Catastrophe Ethics: Causal Inefficacy & the Possibility of Practical Moral Guidance

Abstract:

For the last two decades, philosophers have debated whether the seeming fact that our individual actions cannot have a meaningful impact on pressing moral problems like climate change implies that we have no relevant duties. If, that is, no amount of refraining from flying will have a meaningful impact on the harms of climate change, could I really have a duty to reduce or eliminate luxury air travel? This is what is often called the problem of causal inefficacy. In this talk, I want to move past this discussion in order to focus on a related concern: namely, whether any account of individual moral responsibility in the face of massive, collective threats can generate actionable, practical guidance. The question is important, I argue, because if we rescue an account of moral responsibility in the face of catastrophe, the sheer number of constant catastrophes that we do or can contribute (infinitesimally) to implies an overwhelming moral responsibility to act in an overwhelming number of (often incompatible) ways. Thus, responding to causal inefficacy is not a solution to our moral life; it is a new problem. Here, I will address that new problem by proposing a novel framework for moral justification that can help us to understand and organize our responsibilities to respond to massive, collective threats.

Sandra Shapshay

October 17th, 2025

In-Person

2PM-4PM, CTIHB 459

The Pragmatic Picturesque: The Case of Freshkills Park on Staten Island

Abstract:

The aim of this paper is to shed some light on current controversies surrounding the creation of ‘landfill’ or ‘garbage’ parks by placing them in historical perspective. By tracing the origins and development of the large, urban public park—in the European and American context—I hope to show that the landfill park is on the vanguard of a pragmatic picturesque tradition dating back to the early 19th c. in which parks are utilized to address social and environmental problems. Focusing on the Freshkills Park project on Staten Island in New York City, I shall argue that the creation of a landfill park is indeed an important way to address such problems today, but that to do effectively, it should function simultaneously to memorialize as well as remediate the socio-environmental devastation that lurks just below the surface.

Carolina Flores

November 22nd, 2024

In-Person

2PM-4PM, CTIHB 459

Beyond misinformation: Online distortions of epistemic agency

Abstract:

Social media is often blamed for contemporary epistemic pathology by spreading misinformation. I argue that social media makes a different, underappreciated contribution to epistemic pathology: it reshapes how we interact with evidence, not just what evidence we have. Specifically, I argue that algorithmic-driven mainstream social media inculcates and habituates agents to new, and often epistemically detrimental, epistemic styles. I discuss key design features of major online platforms that contribute to this, consider examples, and argue that we should worry about this for both epistemic and political reasons.

Luca Ferrero

October 31st, 2025

In-Person

2PM-4PM

Fouls, Fumbles, and the Fate of the Agent: Constitutivism for Imperfect Players

Constitutivism holds that the norms governing agency derive from what it is to be an agent: one must play by certain rules, on pain of falling out of the game altogether. Yet this vision risks leaving no room for imperfection—if the rules are constitutive, how can there be bad agents or defective actions that remain genuinely agential? This talk explores that tension through two contrasting models. In the legal or grammatical model (“legal chess”), illegality constitutes collapse: fouls threaten existence. In the functional model (organisms, artifacts), defects are possible and gradable, but they carry no existential force—mere fumbles. I argue that rational agency involves a hybrid structure: a kernel of perfect legality nested within a system capable of functional self-correction. Within this framework, some “bad moves” count as intelligible fouls—violations that remain internal to the game because they are self-repairing. The result is a form of augmented constitutivism that preserves the existential bite of constitutive standards while accommodating the resilience, defectiveness, and corrigibility of imperfect players like us.

Michael Cohen

November 7th, 2025

On Zoom

2PM - 4PM

Knowledge with and without belief